This is the first of three posts relating to the historic evolution of our founders’ notion of the United States as an exemplary nation, a beacon illuminating the possibilities of freedom. The second focuses on the nineteenth century, when our ideals as the first post-colonial nation would run into the realities of our continental expansion. The third considers the early-twentieth-century rivalry of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, advocating alternative visions of the United States as a global power that persist into the twenty-first century.

For my own part, I see little glory in an Empire which can rule the waves and is unable to flush its own sewers. —Winston Churchill

I am insisting on nationalism against internationalism. —Theodore Roosevelt

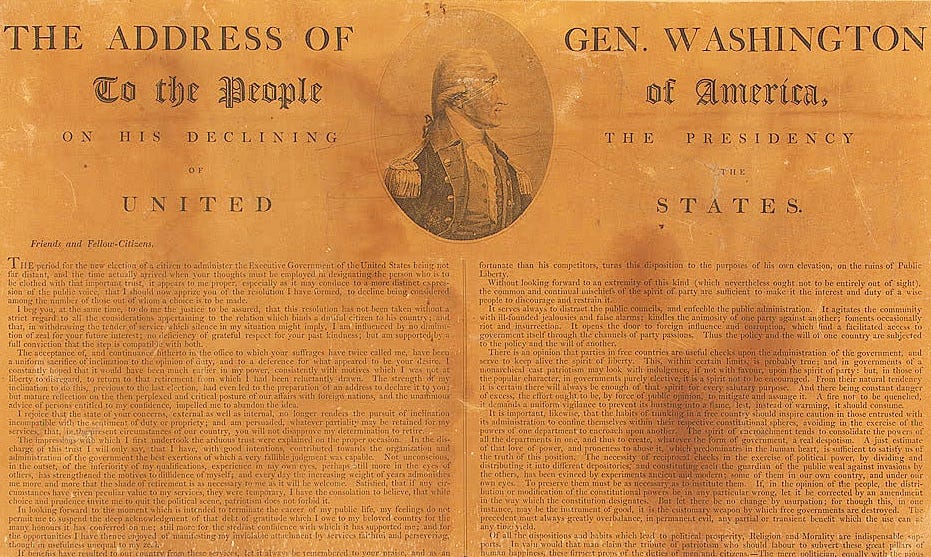

The United States of America is the first post-colonial nation. In declaring our independent nationhood, our founding generation was cognizant that it was in acting pursuant to English political ideals that were unrealized in imperial governance in the New World.

The generation of 1776 recognized that the American experiment, no matter how well intended and designed, could fall prey to the forces that corrupted the British empire. Serendipitously, the first volume Edward Gibbon’s monumental The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was published in early 1776, mere months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, also released in the spring of 1776, included expressions of concern about the sustainability of a political economy reliant on colonial possessions.

Setting a pattern that persists to the present, the Declaration provided a mission transcending national self-interest. Our revolution would not be one-and-done. It would not be simply about us. The signatories set in motion an experiment of uncertain destination and universal application.

Each succeeding generation of Americans has sought to advance our ideals. That pursuit has spurred progress while illuminating spaces where our practices fall short. This includes our interactions with other nations as well as with one another at home. To what extent are we a “city on a hill,” whose revolution example is a gift to people everywhere seeking self-sovereignty and advancement? Will our success incline us toward empire, despite our defiance against imperial subjugation? Can the American experiment survive the emergence of an American empire?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The New Nationalist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.